Peer Review Information on Virtual Reality Therapy for Ptsd

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for Armed forces Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review and Focus Group

i

Psychosocial Rehabilitation Laboratory, Centre for Rehabilitation Inquiry, School of Health, Polytechnic Institute of Porto, 4200-072 Porto, Portugal

ii

Occupational Therapy Department, Santa Maria Health School, 4049-024 Porto, Portugal

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Academic Editor: Xudong Huang

Received: eleven November 2021 / Revised: 27 December 2021 / Accustomed: 29 December 2021 / Published: i January 2022

Abstract

Virtual reality exposure therapy (VRET) is an emerging treatment for people diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) due to the express accessibility of psychotherapies. This research aims to make up one's mind the guidelines for developing a Virtual Reality–War Scenario program for War machine veterans with PTSD and encompasses 2 studies: Report one, a systematic electronic database review; Study 2, a focus group of twenty-two Portuguese Military veterans. Results showed a positive impact of VRET on PTSD; notwithstanding, there were no grouping differences in most of the studies. Farther, according to veterans, new VRET programs should be combined with the traditional therapy and must consider as requirements the sense of presence, dynamic scenarios, realistic feeling, and multisensorial experience. Regardless, these findings suggest VRET as a co-creation process, which requires more controlled, personalized, and in-depth enquiry on its clinical applicability.

i. Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health problem that may occur in people who have experienced or witnessed a traumatic event such every bit a natural disaster, a severe accident, a terrorist act, sexual assault, or state of war/combat [1]. The prevalence charge per unit of PTSD in the full general adult population is currently 6.8% in the United States and 0.six–half dozen.seven% in Europe [2,3]. PTSD negatively impacts patients' daily lives and is associated with a higher mortality risk [4].

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V), PTSD includes the presence of repeated and unwanted intrusive symptoms about an event (memories, dreams, flashbacks), persistent avoidance of the stimuli associated with it (thoughts, emotions, places), negative changes in knowledge and mood (distorted noesis, beliefs or expectations), and significant changes in activation and reactivity (hypervigilance, difficulty in sleeping, irritable beliefs) [5]. The development depends on numerous risk factors related to individual's psychological and cognitive vulnerabilities, poor social and family unit back up [6,seven,8], prior mental disorders, depression socioeconomic status, low education level, gender (i.due east., female), immature age at the time of the trauma, and minority condition [9]. In addition, there has been an expanding body of literature on the genetic chance factors associated with the development of PTSD [10]. It seems to be more severe and persistent when the stressful event is caused by humans and combat-trauma related [xi].

In fact, research over the terminal decade has shown that armed forces personnel exposed to war-zone trauma have a high risk for developing PTSD [12]. According to different studies, the prevalence rates of PTSD among soldiers and veterans tin can accomplish thirty% [xiii]. In a 2017 report involving 5826 U.s.a. veterans, 12.nine% were diagnosed with PTSD. [14] This is a strikingly loftier rate compared to the incidence of PTSD among the general population. In what concerns the Portuguese reality, research noted that 30% of Portuguese soldiers in the 14 years of the Portuguese colonial war had chronic PTSD [15].

In recent years, some studies take identified different types of potentially traumatizing war zone experiences that may lead to agin psychological issues such as PTSD: committing or observing a moral injury, threats to life, atrocities or abusive violence, traumatic loss, perceived threat, and hostile environments [16]. Combat-related PTSD is unremarkably characterized by unwanted memories, unpleasant dreams or nightmares, flashbacks, and physiological and psychological distress in response to these trauma war-zone experiences. Information technology is also frequently associated with emotional dysregulation, social maladjustment, maladaptive cognitions, acrimony management difficulties, and impulsive or vehement behavior [17].

Electric current systematic reviews with meta-analysis [18] and guidelines [19,20,21] recommend trauma-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), cognitive processing therapy (CPT), cognitive therapy (CT), Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), and particularly exposure therapy as effective PTSD therapies. Considering in vivo and imaginal exposure therapy inadequacy and limitations for gainsay-related PTSD treatment, Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET), based on the cadre principles of Prolonged Exposure and Cognitive Processing Therapy, has become an alternative, with promising results in this ambit [22,23,24,25]. In add-on, copious evidence shows that virtual reality environments produce emotional, physiological, and behavioral responses like to those observed in real-life situations [26].

Virtual reality exposure therapy enables the emotional appointment of patients with combat-related PTSD during exposure to a virtual war surround, bypassing avoidance symptoms and facilitating control on the therapist'south part. The sense of presence provided by an ecologically valid, highly interactive, and multisensory virtual surround facilitates the emotional processing of memories related to the traumatizing war-zone experiences [27,28,29]. This approach allows standard, gradual, and personalized exposure to the traumatic environs according to each patient's needs and tolerance. Information technology carries the advantages of increased control over stimuli, the possibility to echo exposure infinitely, and the unique option to simulate environments that challenge patients according to their specific needs [30]. Several studies too point out that VRET is more effective, saving time and costs in treating various anxiety disorders, including specific PTSD. These results encourage and promote patients adherence to the VRET-based approach [31]. Nevertheless, at that place is express research bachelor about the development and efficacy of these therapies, which does not allow this innovative solution to be suggested by clinicians.

This study aims to analyse the efficacy of VRET for PTSD while determining the guidelines for designing a Virtual Reality–War Scenario programme for Portuguese Armed Forces veterans diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

ii. Methods

ii.i. Written report 1

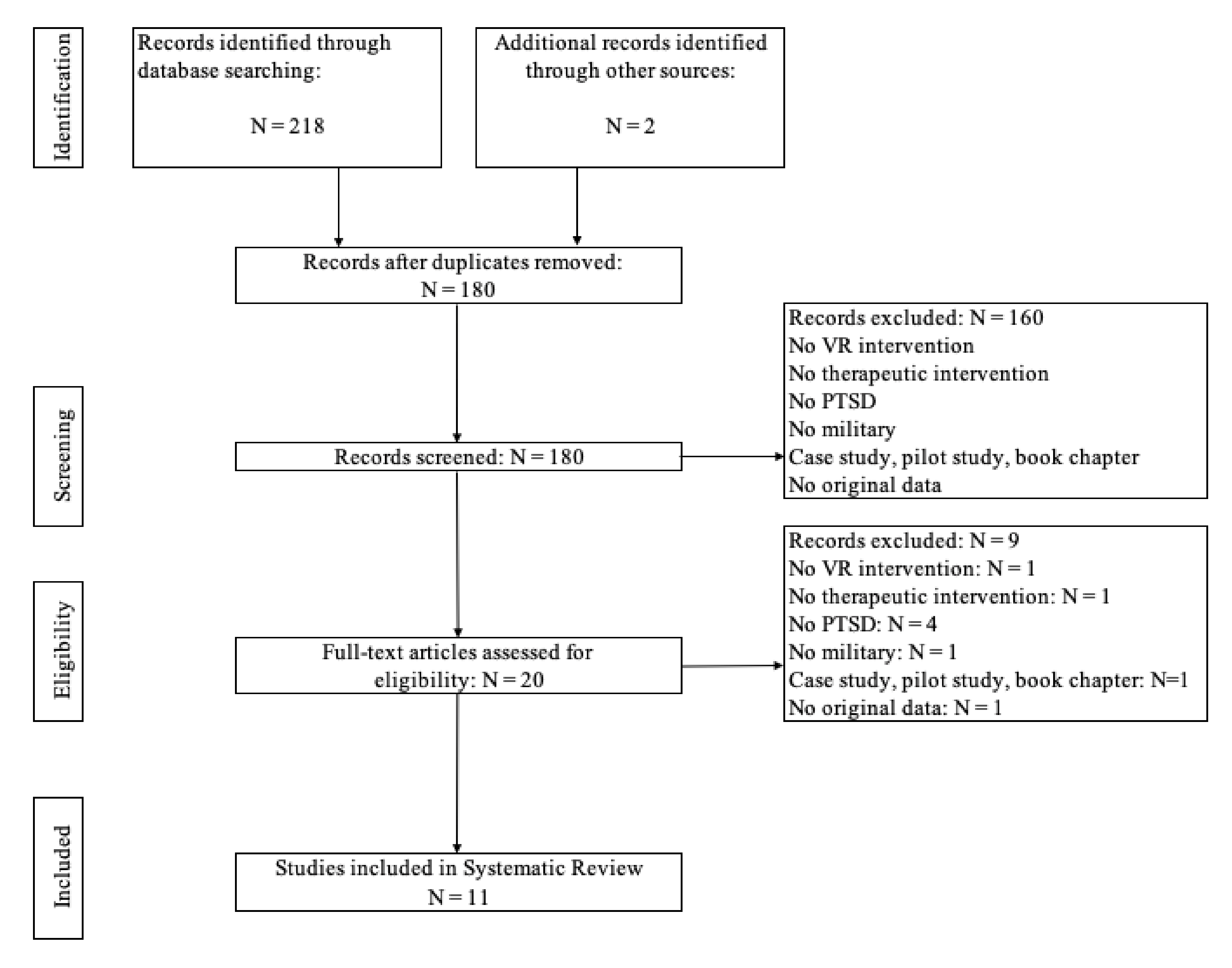

A systematic review was conducted to gather assumptions and requirements for designing a VRET programme for Armed Forces veterans diagnosed with Postal service-Traumatic Stress Disorder. This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-assay (PRISMA) guidelines [32]. In Feb of 2021, searches were performed in the following electronic databases: B-on, PubMed, PTSDPubs, Clinical trials, and Cochrane Library. The search terms ["Virtual Reality"], ["PTSD"] and ["Veterans"] were used, using the term "AND" between each i, and included existing articles written in English. In add-on, we used the references of papers included in our review to search for other relevant publications.

Inclusion Criteria—one. VRET was used every bit a therapy or equally a supplement to evidence-based treatment to reduce PTSD symptoms; 2. The study focused on the efficacy of VRET to reduce PTSD symptoms; 3. PTSD symptoms were assessed with validated PTSD cess instruments; self-reported or clinician-rated; four. VRET minimally consisted of either an Head-mounted display—HMD that immersed a patient into a digital environment or a large projector screen that displayed the virtual environment.

Excluded Criteria—i. Published in languages other than English; 2. Not-experimental/not-RCT studies were excluded (Figure 1).

In the research, 218 studies were identified, and the kickoff step was to remove duplicate titles. Then, the titles and abstracts were reviewed by ii independent researchers. The consummate article was evaluated in example of doubtfulness about the study's inclusion just by its abstract. For studies that met the eligibility criteria, the full text was revised, and 11 papers were accepted for review, because the eligibility criteria. A data-charting grade was developed to determine which variables to extract, and Figure 1 outlines the written report pick process. Bibliographic information, design, purpose, participants, measures, interventions, VR technology, and fundamental findings were collected and are summarized in Table 1.

Quality Assessment

Each selected commodity was assessed using a systematic quality cess to determine the quality of reporting and the presence of methodological bias (check the Supplementary Materials).

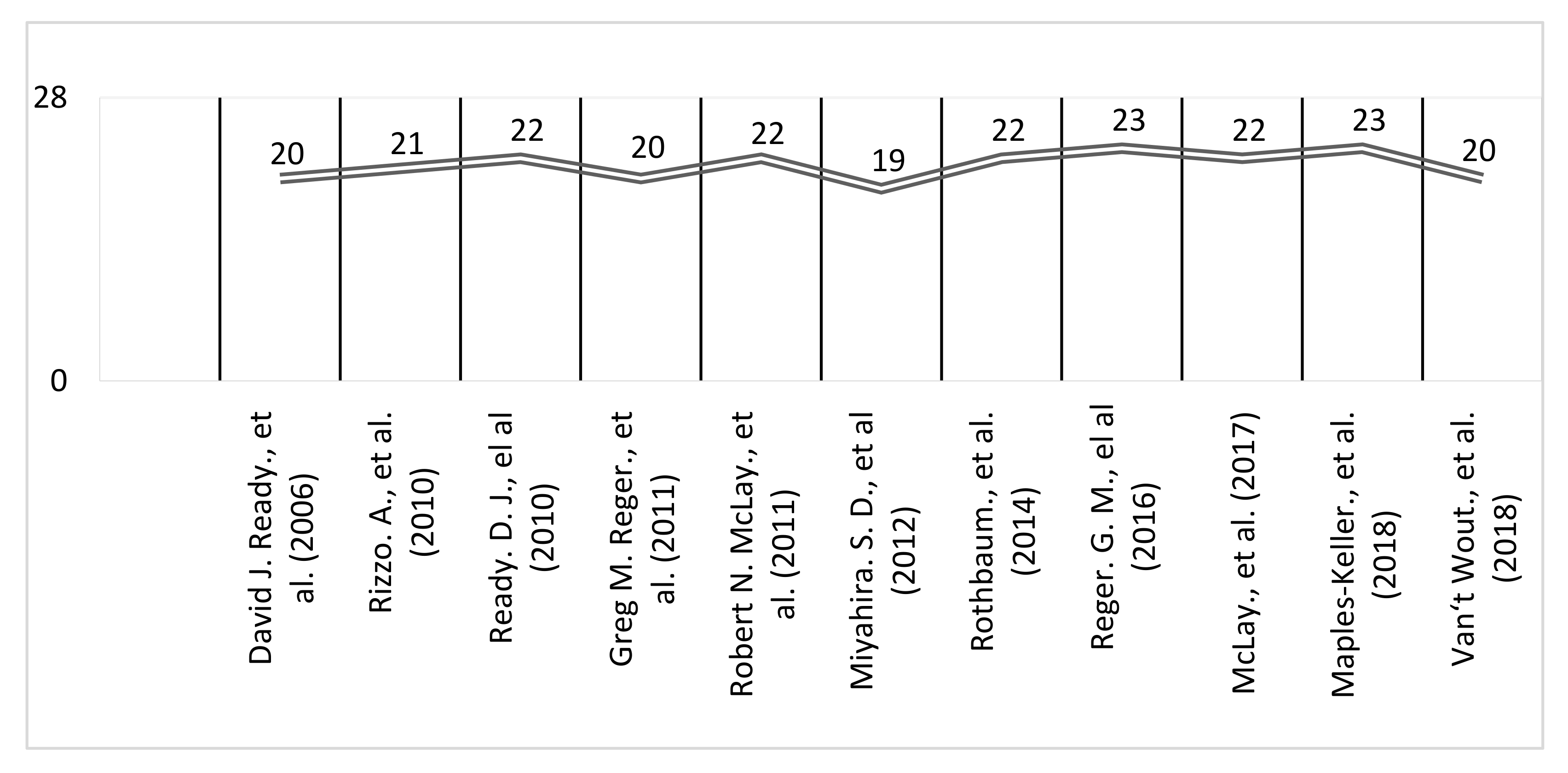

Studies were assessed for quality using the Downs and Black checklist. The checklist included four categories for evaluation: reporting, external validity, internal validity/bias, and internal validity/confounding. The methodological quality of all the included studies was assessed individually [33]. The score initially proposed for question 27, "Did the study have sufficient ability to observe a clinically important effect where the probability value for a difference due to adventure is less than v%"? underwent a small change. Instead of the five possible scores presented by the original authors, the results were contradistinct to 0 or 1, based on whether the authors conducted a power analysis to detect a significant clinical effect (of at least 0.eighty, with alpha at 0.05), with a score of 0 significant "no" and 1 meaning "yep". Thus, the ratings of all 28 items were either yes (=1) or no/unable to determine (=0), except for detail five, in which the scores varied as yes (=2), partially (=one), and no (=0). Nomenclature of the final scores barbarous into iv categories: fantabulous (26–28), adept (20–25), fair (15–19), and poor (xiv and less).

According to the Downs and Black scores, 10 of 11 studies (N = 10/xi) 90.90% had a result of good (20–25), and only one (N = 1/xi) nine.09% had a result of fair (19 points) (Figure 2).

ii.2. Study 2

The objective of the focus group was to examine the thoughts, feelings, perceptions, and concerns about using Virtual Reality (and developing war scenarios), too every bit its possible utilize in the treatment of armed forces veterans with war trauma. The eligible participants were Armed services veterans with war trauma (PTSD) involved in colonial war or peace missions. Participants were enrolled through a peer support grouping (Núcleo da Liga de Ex-Combatentes de Lamego). Authorization was requested from high military ranks to proceeds access to this grouping, and after the request was accepted, 22 interested participants were contacted by telephone. Participants were all war veterans who served in the Colonial War (Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea) and NATO peacekeeping missions (Timor, Iraq, Bosnia, Serbia, and Afghanistan). All were male with a hateful historic period of 67.5 years old, (age range 55–80 years).

The effective sample received written and verbal information about the study aim and procedures. Earlier data collection, all participants gave written informed consent and exact permission to tape the focus grouping session. The focus group took place at the Special Operations Troops Center Library and by videoconference via Zoom.

Group members were asked to introduce themselves and to land what they knew about VR. They were then asked to summarize their military histories. This introduction established the context of each person'south participation.

Data Collection

The focus grouping was conducted using semi-structured interview guidelines that included open questions about RV (war scenarios). Participants were asked to talk well-nigh: (one) What practice they know about VR; (2) How they see VR equally a therapeutic method; (3) VR Scenario characteristics; and (4) VR Barriers.

Some examples of semi-structured interview questions include (ane) How would they see, in full general, the use of VR to help deal with PTSD?; (2) What characteristics should the virtual environment take to unfold the stimulation?; (3) What narrative should information technology present? Where should yous go? What is happening? When? With whom?; (iv) Of import topics: narrative; context; characters; (5) Should the scenario include different static levels?; (6) How should the instructions come up up along the game? (7) How long should the game final?; (8) What precautions should we accept?; (ix) What are the advantages and disadvantages that are identified in its use?

The focus group was audio-recorded, and the data collected was encoded. Like codes were grouped and organized into major themes and topics in the next step. The categories respected the criteria of relevance, homogeneity, objectivity, and purpose.

The study was canonical past the Ethics Commission of the Schoolhouse of Health, Polytechnic of Porto (CE0064B).

three. Results

three.ane. Study i

Tabular array ii summarizes the study and treatment characteristics of the 11 articles included in this review. All selected papers were quantitative and experimental studies [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]; the sample size was 641 subjects. The dropout rate was 160 subjects, with 481 subjects remaining in the treatments. Patients were predominantly male (96.vii%). The mean age ranged from eighteen to 62 years across studies. Studies included active-duty soldiers and veterans with combat-related PTSD. All selected studies for this review were carried out in the United States.

In 8 of the nine studies, the reduction in PTSD symptom severity was operationalized by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (two of the studies did not reveal which musical instrument was used). In one study, the reduction in PTSD symptom severity was operationalized by the PCL-v—PTSD checklist for DSM-v. Two studies [41,43] used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM—Four) as the musical instrument for PTSD diagnosis; two [35,36] used the PTSD Checklist, Military Version (PCL—G); 4 [34,37,42,43] used Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM—5); one study did not refer to the Instrument for PTSD diagnosis (32); and finally, the remaining two [39,40] used Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM—Iv—TR).

In all selected studies, the therapeutic framework was prolonged exposure. PE is an exposure therapy for PTSD that received the most empirical show for its efficacy. It is highly effective for patients with a broad variety of traumatic experiences. In a series of randomized controlled trials, PE demonstrated major treatment effects compared to waitlist (WL) command groups and like results compared to other active treatments, such every bit stress inoculation training, cognitive processing therapy, eye motility desensitization, and reprocessing [44].

Most of the studies (45.45%) used virtual Iraq/Afghanistan. The Iraq/Transitional islamic state of afghanistan VR system was developed by the Institute for Creative Technologies at the Academy of Southern California [45]. This tool includes a clinician's interface that allows the therapist to customize the VR surround in real-time to match the patient'south trauma memory characteristics. Equally the patient recounts his/her trauma memory during imaginal exposure, the therapist fits the environment [39,40,41,42,43].

These virtual environments included comprehensive prototype scenarios of combat-related PTSD experiences, such every bit riding in a Humvee through a desert [seven]. The software has been designed and then that users can be "teleported" to specific locations within the metropolis, based on a determination as to which components of the environs most closely match the patient'due south needs relevant to their private trauma-related experiences [35].

The caput-mounted display, HMD, used for 63.63% of the studies was the eMagin z800 [35,36,39,xl,41,42,43].

The sessions generally lasted between 30 and 120 min, and the average was 76.3 min per session. The number of sessions was betwixt three and 20. Four studies included at-home in vivo exposure exercises (e.grand., listening to audio recordings of each VR exposure in the retention) [34,35,41].

Six out of eleven studies (54%) explored whether the efficacy of VRET may be increased through additional medication [28,36,39,40,42,43]. Study [42] examined whether the administration of dexamethasone improved the efficacy of VRET compared to placebo treatment. Study [39] analyzed to what extent D-cycloserine and alprazolam influenced the effectiveness of VRET compared to a placebo group.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics = 11 included studies.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics = eleven included studies.

| References | Country | Instrume for PTSD Diagnosis | Chief Result Variable | Study Design | Sample and Trauma Type | Participants | Dropout | Intervention | Time Points of Measurements and Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ready, David J., et al. (2006) [34] | USA | DSM-IV | CAPS | Trial | Vietnam veterans with PTSD. | Total participants: N = 21 Male person: 100%; | Full: N = 6; | VRET | Measurements: Pre-, mail service-, and iii- and 6-month follow-ups; Event size (CAPS) All patients scored on the 3- and 6-month follow-up assessments were below their pretreatment scores (range −15 to −67%), p < 0.0001. Summary: All 14 patients showed reductions in PTSD symptoms compared to baseline by the 3-calendar month follow-upward assessment. These gains were maintained in 10 of the 11 patients who completed the 6-calendar month follow-up assessment. In half-dozen of these patients, the CAPS scores continued to decline betwixt the immediate post-treatment assessment and the 6-month assessment. |

| Rizzo. A., et al. (2010) [35] | USA | PCL-M | CAPS | Trial | Active duty soldiers. | Total participants: N = 20 Male person: 90%; Female = 10%; Mean age = 28 years; Age range: 21–51 years; | Total: Due north = 6; | VRET | Measurements: Pre-, postal service- Issue size (CAPS) Pre-/post-PCL-M scores decreased in a statistical and clinically meaningful way; mean (SD) values went from 54.iv (9.7) to 35.6 (17.4). Paired pre-/mail service-t-examination assay showed these differences to exist significant (t = v.99, df = 19, p < 0.001). Summary: 80% of the treatment completers in this VRET sample showed both statistically and clinically meaningful reductions in PTSD, anxiety, and low symptoms, and anecdotal evidence from patient reports suggested that they saw improvements in their everyday life situations. These improvements were too maintained at the 3-month post-handling follow-up. |

| Ready. D. J., el al (2010) [34] | Usa | DSM-5 | CAPS | RCT | Vietnam veterans with PTSD. | Total participants: Due north = 11 VRET: N = half-dozen Male: 100%; Hateful historic period = 57; Age range: 53–61 years; PCT: N = five Male person: 100% Mean age = 58; Historic period range: 55–62 years; | Total: N = 2; VRET: N = 1; PCT: N = one | VRET vs. PCT | Measurements: Pre-, post-, and 6-month follow-ups Effect size (CAPS) Summary: VR—31.8 (SD1⁄439.1) from pre- to mail service- and of 25.0 (SD one⁄4 28.1) from pre- to follow-upwards, Cohen's of 0.28 and 0.56; BDI—5.0 (SD 1⁄4 8.vii) from pre- to post- and of two.3 (SD 1⁄4 7.eight) from pre- to follow-up. Pct—23.0 (SD1⁄421.ix) from pre- to mail service- and of 13.0 (SD ane⁄4 xi.3) from pre- to follow-up; Cohen of 0.0 and −0.24; BDI—of 5.0 (SD1⁄47.5) from pre- to mail- and of 4.3 (SD i⁄4 8.eight) from pre- to follow-upwards. Combining groups—CAPS scores from pre- to mail- (t 1⁄four ii.seventy, p < 0.05) and from pre- to 6-calendar month follow-up (t1⁄42.58, p < 0.05). No statistically significant improvement in CAPS or BDI scores when individual handling conditions were isolated. Summary: possible value of VRE while pointing out that the chief difficulty with further investigation of this handling model with older veterans is participant recruitment. |

| Reger, Greg 1000., et al. (2011) [36] | USA | PCL-M | CAPS | Trial | Active duty soldiers. | Total participants: North = 32 Male: 96%; Mean historic period: 28.8, Gender: n.r. 75% were diagnosed with PTSD (n = xviii); | Total: N = 8; | VRET | Measurements: Pre-, mail- Effect size (CAPS); Pretreatment PCL-M (M = sixty.92; SD = xi.03), patients receiving VRE reported a statistically meaning drib in PTSD symptoms (Grand = 47.08; SD = 12.70), t (23) = half dozen.53, p < 0.001, d = one.17; At post-treatment, differences on the PCL-M were no longer significant between those with PTSD (M = 49.72; SD = 13.twenty). Summary: Patients receiving an average of 7 sessions of VRE reported statistically and clinically significant reductions in self-reported symptoms of PTSD. |

| McLay, Robert N., et al. (2011) [37] | USA | DSM-5 | CAPS | RCT | Agile Duty military personnel with gainsay-related PTSD. | Total participants: N = xx, VR-Become: N = 10 Male: 90% Mean age: 28.viii; Gender: 22–43; TAU: Northward = 10 Male: 100%; Mean age: 28; Gender: 21–45; | VR-Go: North = north.r; TAU: N = n.r; | VR-Get vs. TAU | Measurements: Pre-, post-, and 10-week follow-upwards; Effect size (CAPS); VR-GET: N = 10, (70%) of these showed a 30% or greater improvement in the CAPS. TAU: N = 10, Ane (11.one%) of the 9 returning participants receiving TAU showed > xxx% improvement on the CAPS. Chi-square for the treatment response comparison betwixt VR-GET and TAU was 6.74, p < 0.01. With Yates correction w2 1⁄4 iv.54, p < 0.05, relative risk was 3.21, with 95% confidence interval 1.xviii to 8.72. Pre-vs. mail-handling, p < 0.001), but non grouping (p > 0.05). There was a significant time-past-group interaction (p < 0.05). In that location was no significant departure between VR-GET and TAU mean CAPS score before or after treatment, just there was a meaning deviation in the hateful CAPS change score over the course of treatment (35.4 vs. nine.4, p < 0.05). Summary: 70% of participants who received VR-GET showed a clinically significant (>30%) improvement in their PTSD symptoms after 10 weeks of treatment. This was a significantly (p < 0.05) college percentage than the 12.5% of participants who showed clinically significant responses in usual handling. |

| Miyahira. S. D., et al. (2012) [38] | Usa | n.r. | CAPS | RCT | Active duty service members with PTSD symptoms who participated in armed forces operations in Iraq or Afghanistan. | Total participants: North = 99 Male: N = 94 Female: N = 5 VRE = 12 MA = ten | Total: Due north = 77 | VRE vs. MA | Measurements: Pre-, post- Effect size (CAPS); Significant subtract over time on the CAPS Benchmark C (avoidance/numbing symptoms) in the VRE group (F (i,xx) = 6.03, p = 0.02); The VRE group scored significantly lower on the CAPS Criterion C compared to the MA group at post- procedures (F (ane, 20) = eight.705, p = 0.008). Summary: VR exposure may be effective in reducing some PTSD symptoms in active duty service members returning from combat. |

| Rothbaum., et al. (2014) [39] | U.s. | DSM-IV-TR | CAPS | RCT | State of war veterans with Iraq and Afghanistan deployment; Gainsay-related PTSD symptoms. | Total participants: N = 156; Males = 94% Mean historic period: 35.1; Gender: 148; VR treatment group (VRET with DCS): n = 53; Males = 92% Mean age: 34.ix; Gender: 49; Active command group (VRE with Alprazolam): n = 50; Males = 98%; Hateful age: 36.two; Gender: 49 Control group (VRET with placebo): n = 53; Males = 94%; Mean historic period: 34.iii; Gender: 50; | Total: N = 59 (37%); VR treatment group (VRET with DCS) North = 25 (47%); Agile command group (VRET with Alprazolam): N = 15 (thirty%); Control grouping (VRET with placebo) N = nineteen (35%); | VRET with DCS vs. VRET with Alprazolam vs. VRET with Placebo | Measurements: Pre, post, 3-, six-, and 12-month follow-ups; Effect size: n.r. and northward.a.# Summary: All groups decreased significantly on the CAPS. The effect maintained over 12 months of follow-upwards. At post-treatment, at that place was no pregnant divergence between D-cycloserin and the placebo group for the CAPS. However, there was a meaning difference favoring placebo over alprazolam regarding the CAPS at mail-treatment. |

| Reger. Yard. M., et al. (2016) [40] | USA | DSM–IV-TR | CAPS | RCT | Active-duty soldiers. | Total participants: Northward = 162; WL: North = 53; Males = 98.15%; Hateful historic period: thirty.39 (half dozen.45); PL: Northward = 51; Males = 94.44%; Mean historic period:thirty.89 (seven.09); VR: N = 52; Males = 96.30%; Mean historic period: 29.52 (half dozen.47); | Full: N = 6 | VRE vs. PE | Measurements: Pre, midtreatment, mail service, 12-week and 26-week; Event size (CAPS); VRE—Pre, 80.44 (xvi.23); 26-calendar week, 53.50 (28.07); PE—Pre, 78.28 (16.35); 26-week, 38.33 (28.49); WL—Pre, 78.89 (16.87); 26-week, n.r. Summary: Results extend previous show supporting the efficacy of PE for active-duty military personnel and raise of import questions for future enquiry on VRE. |

| McLay., et al. (2017) [41] | USA | DSM-IV | CAPS | RCT | Agile duty military members with by Iraq and Afghanistan deployment; Gainsay-related PTSD symptoms. | Total participants: N = 81; Males = 96.three%; Hateful historic period: 32.five; Gender: 78; VR treatment group (VRET with immersive technology): n = 43; Males = 93% Hateful age: 33; Gender: forty; Agile command group (VRET with non-immersive engineering): due north = 38; Males = 100%; Hateful age: 32; Gender: 38; | Total: N = 7 (8%); VR handling group (VRET with immersive applied science): N = 7 (xvi%); Active control group (VRET with not-immersive technology): N = 0 (0%); | VRET with immersive technology vs. VRET with non-immersive applied science | Measurements: Pre, post, and 3-calendar month follow-upwards Effect size (CAPS): Hedges' gpost = −0.33# (favoring VRET with non-immersive engineering) Hedges' g3month = 0.15# (favoring VRET with immersive technology) Summary: Significant decrease on the CAPS maintained over iii-calendar month follow-up. No significant differences betwixt groups were found. |

| Maples-Keller., et al. (2018) [42] | The states | DSM-5 | CAPS | RCT | War veterans and agile duty personnel with past Iraq and Transitional islamic state of afghanistan deployment; Gainsay- related PTSD symptoms. | Full participants: N = 27; Males = 100%; Mean age: 35.iv, Gender: 27 VR handling group (VRET with dexamethasone): N = xiii; Males = 100%; Hateful age: northward.r. Gender: 13; Active control group (VRET with placebo): N = fourteen; Males = 100%; Mean age: n.r. Gender: fourteen; | Total = 3 (12%), VR treatment group (VRET with dexamethasone): N = 0 (0%); Active control group (VRET with placebo): North = 3 (25%); | VRET with dexamethasone vs. VRET with placebo | Measurements: Pre and mail Effect size (CAPS): Combined sample Cohen'south dpre-mail service = n.r. Summary: Significant decrease in the CAPS for mail-handling merely no meaning differences between groups. |

| Van't Wout., et al. (2018) [43] | USA | DSM-five | PCL-v | RCT | War veterans with Republic of iraq and Afghanistan deployment; Combat-related PTSD symptoms. | Full participants: N = 12; Males = 100%; Mean historic period: 40.five; Gender: 12 VR treatment group (VRET with tDCS): Due north = due north.r. Hateful historic period: n.r. Gender: n.r. Active command group (VRET with sham tDCS): N = n.r. Mean age: northward.r. Gender: n.r. | Full = northward.r. VR treatment group (VRET with tDCS) Northward = north.r. Active command group (VRET with sham tDCS) N = n.r. | VRET with tDCS vs. VRET with sham tDCS | Measurements: Pre, post, and ane-calendar month follow-up Result size (PCL-5): Hedges' gpost = 0.20# (favoring VRET with tDCS) Cohen's d1month = 0.37 Summary: Both groups demonstrated significant reductions in PCL scores. There were no significant differences betwixt groups at post fourth dimension measurement, just VRET with tDCS was superior to VRET sham tDCS at 1-month follow-up. |

Table 2. Results of the qualitative assay for each study.

Table 2. Results of the qualitative analysis for each written report.

| References | Therapeutic Framework | Period of Fourth dimension | Number of Sessions | Medication | Homework | Hardware | Software |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| David J. Fix et al. (2006) [34] | PE | Ii 90-min sessions | 8 to xx | north.r. | Yes; Breathing do for stress management and was asked to practice this practice daily | n.r. | Virtual Vietnam |

| Rizzo, A et al. (2010) [35] | PE | 2× weekly, 90–120-min sessions over 5 weeks | x | northward.r. | Yes; Kickoff item in a hierarchical list nigh a traumatic effect and listening to the audiotape of their exposure narrative from the about contempo session | HMD—eMagin z800 | Virtual Iraq |

| Gear up, D. J., et al. (2010) [34] | PE | due north.r. | 10 | due north.r. | due north.r. | north.r. | northward.r. |

| Greg M. Reger et al. (2011) [36] | PE | 90 min | three to 12; | Yep—77% N = 16; Antidepressants—North = 12; Prazosin—N = 8; Slumber aids—Due north = 7; Quetiapine—N = 1; Lamotrigine—Due north =one; Hydroxyzine pamoate—N = 1 | Yes; Listening to audio recordings of each VR exposure to the memory | HMD—eMagin z800 | Virtual Iraq |

| Robert Due north. McLay et al. (2011) [37] | PE | VR-Go—1× per calendar week for up to 10 weeks; TAU—ten weeks | VR-GET–10 TAU—xiv | Aye; psychotropic medications | n.r. | northward.r. | n.r. |

| Miyahira, S. D., et al. (2012) [38] | PE | two sessions per week for 5 weeks | 10 | north.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Rothbaum et al. (2014) [39] | PE | ninety min; 45 min | half dozen; 5 | Yep; D-cycloserine (50 mg); Alprazolam (0.25 mg); The placebo medication 30 min earlier exposure | n.r. | HMD—eMagin z800 | Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan |

| Reger, Thou. M., et al. (2016) [twoscore] | PE | 90–120 min | x | Yes—north.r. | No—n.r. | HMD—eMagin z800 | Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan |

| McLay et al. (2017) [41] | PE | ninety-min 30–45 min | 8 to 12; five to 9 | due north.r. | Aye—Confronting existent life stresses in vivo; | HMD—eMagin z800 | Virtual Iraq/Transitional islamic state of afghanistan |

| Maples-Keller et al. (2018) [42] | PE | ninety-min of 7 to 12 weeks; 30–45 min | 7 to 12; half dozen to 11 | Yes— Dexamethasone (0.5 mg) or placebo the night before virtual exposure | north.r. | HMD—eMagin z800 | Virtual Iraq/ Afghanistan |

| Van't Wout et al. (2018) [43] | PE | xc-min of 2 weeks; thirty–45 min | 6; 6 | Yeah—due north.r. | n.r. | HMD—eMagin z800 | Virtual Republic of iraq/ Afghanistan |

3.2. Study 2

One of the authors moderated the focus groups that were conducted for virtually ninety min. The debate was serene, flowed naturally, and the intervention of the researcher/moderator was hardly necessary because the points that needed to be addressed were divers from the beginning. The sound-recordings were transcribed verbatim and reviewed for accurateness in transcription. Two independent researchers conducted the coding and resolved discrepancies through analysis of the raw data and input from experts on the topic. Data assay was based on the technique of qualitative content analysis, and software webQDA was used.

Content analysis emerged on three primary themes: (ane) Importance of VR in PTSD, (2) VR software, (three) VR Barriers (Table three).

VR Potential—None of the participants knew well-nigh Virtual Reality, much less that it could be used as a therapeutic tool in PTSD. Later on a brief caption about VR, how it can be used, and its significant advantages, all participants agreed that it would exist innovative and pertinent to technology combined with therapy. 1 of the erstwhile combatants said, "the technology finally came to us", which shows the receptivity of this group to this therapy.

VR software—The interdisciplinary nature of VR and its evolution permit the user's immersion, navigation, and interaction with a given platform or scenario generated by a computer to exist explored past various man senses and feelings, allowing the user to exist in three dimensions: visual, sensory, and kinesthetic [46].

All participants agreed that hearing, impact, and scent stimuli should be present in a State of war scenario. The smell of rain and wet earth is ingrained in their memories to this twenty-four hours, and afterwards so many years, it is the smell they remember nigh: "The smell of heavy rain"; "The olfactory property of the first rains and the earth". The sense of smell allows a closer approximation with reality in possible take chances preparation sessions or psychological intervention on traumatic events [46].

Immersion was another central cistron and idea present in the focus grouping sessions. It is crucial to have the feeling of presence to create the idea of being in some other place, a identify full of memories, which will make the feeling of involvement. The interest, in turn, is linked to the degree of personal motivation in a detail task or action.

For the sense of presence to be guaranteed, it must ensure sensory fidelity, which corresponds to creating an surround with the highest possible caste of "realism". Withal, making sense of presence is not limited to "showing" and "recreating" scenarios. Information technology also implies interactivity and a psychological component [47]: "The scenario should be dynamic and realistic"; "I want to experience what I felt before, expect and meet my memories, my pain".

The storyline, the quality of the narrative, and its elements are fundamental to the realism that this scenario must accept. There is a military linguistic communication, vesture, weapons, vehicles, fauna, and flora that will take to exist nowadays so that the illusion of presence is complete on four levels: spatial (feeling you lot are in a particular place); corporal (feeling y'all accept a body); physical (being able to interact with the elements of the scenario); and social (existence able to communicate with the characters in the environment) [48]—"The bombing drove away the animal and flora", "The enemy was as well the mosquitoes", "There was no helmet, there were many mines", "We acted in groups", "I slept two years in the bush-league under a fabric tent", and "There were no civilians, anyone who appeared after you left the barracks was considered an enemy".

To provide a more immersive experience, information technology must exist possible for the individual to collaborate and alter the virtual environment in which the person is sensorially inserted, considering his/her emotional state. This alter in the environment should exist linked to the figurer'due south ability to detect the user inputs and instantly change the virtual world according to its actions. This reactive capacity of the computer allows the scenes to change in response to user commands [42]: "We should have pedagogy earlier starting the immersion", "The evolution in the scenario should exist automatic", and "fifteen to 20 min is enough to experience the scenario".

Information technology is essential that the surround created is every bit faithful as possible, which implies that a lot of detail matches the sensory earth. These aspects are central since the user takes several pieces of information from the scenario to locate himself/herself spatially.

VR Barriers—The only bulwark or concern that veterans had was that they were non prepared to "enter" a war scenario again. Before they were physically and psychologically prepared to fight the enemy, they no longer had any training with these skills: "With time, how am I going to react? Before, I was prepared, but now I'm not".

4. Discussion

Summary of Findings

This study explores the effectiveness of VRET for PTSD in veterans and the most advisable requirements for their implementation. According to the review, Virtual Reality for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder handling in former Military combatants seems beneficial. The systematic review revealed that the study of VRET protocols had a positive impact on a range of symptoms, and all treatment gains were maintained at 3, six-, and 12-month follow-ups [34,35,36,37,38,39,twoscore,41,42,43]. However, there were no group differences in most of the studies.

Most of the studies on VRET included 3–20 virtual exposure sessions, lasting 30–120 min. These studies were based on the Emotional Processing Theory (EPT). In this theory, fright is represented in memory as structures made upward of associated stimulus, response, and meaning elements designed every bit a program to avoid or escape danger [49]. Traumatic events modify the basic behavior of an individual since negative behavior almost the earth, oneself, and others increase [49,50].

Since the key in emotion processing theory is to expose and modify its unique fear structure, discharged soldiers can control some of their subversive behaviors resulting from PTSD in a rubber environment and acquire how to solve these situations [51]. VR enables the patient to explore emotions while decreasing the sense of threat. It is essential to monitor anxiety levels through advanced systems and process their sensations and feelings. Any alarm should indicate to the therapist how to manage the intensity of the simulations not to cause worse damage to the patient [14]. One of the advantages of VR is to let the therapist to control moment by moment, documenting and measuring the patient's responses to stimuli [52].

Regarding the guidelines, the evolution of this VR plan should involve graphic models and narratives [14]. All of these factors were considered relevant in the focus group sessions, the narrative being ane of the essential points in creating a realistic State of war scenario for the Armed Forces veterans. The focus group also highlighted that the specific content should exist discussed in a group, then worked on with the VR resources before starting the program and not at the cease. Furthermore, it is essential that the old combatants contact the VR to permit habits and that the adverse furnishings can be supplemented from the beginning. Another crucial factor is the private's initial evaluation earlier exposing himself/herself to the VR, to guarantee that the security weather are reunited for their participation.

The VRET protocols varied according to medication, at-domicile in vivo exposure exercises, number of sessions, and period of time. Continuous monitoring is likewise referred to every bit essential. It avoids demotivation of the participants, which can cause them to give upwards. This monitoring may be passed on as homework (Table ii) [34,35,36,40].

The results showed that HMDs were used in vii studies in terms of the human interface. Detailed analyses revealed that 75% of the HMDs were released in 2005–2006, and the remaining 25% were released in 2012–2013. Therefore, it is necessary to deepen the effectiveness of this technology for a better understanding of its effects [53]. However, VR and its application as well accept limitations. The immersive nature of HMDs creates a potent presence illusion, where users perceive virtual environments (VEs) as existent and not mediated through technology. The major practical issue with HMDs is that users commonly study adverse concrete reactions, including headaches, nausea, dizziness, and heart strain when using them. Collectively, these symptoms represent a status termed simulator sickness, which reportedly affects up to 80 percent of HMDs users [54,55]. Several reviews did not specify the hardware [34,37,38] or software [34,37,38] used in included studies.

Therefore, a solution that addresses discomfort experiences during a user's first HMD exposure is essential to the continued growth and adoption of VR. This visual discomfort of VR tin can lead to handling abandonment. Therefore, besides studying the efficacy of VRET, it is also crucial to investigate the safety of the handling.

The software also imposes limitations (which we intend to address with the requirements survey conducted in the focus group). The software is ofttimes restricted to protocols created that will hinder an adequate virtual environment for the specific needs of each patient or group. Considering of the pre-programmed scenarios, creating a virtual trauma-related environment that completely matches the patient's recounting is impossible. Therefore, breaks in the sense of spatial or social presence and plausibility may occur [56].

The lack of standardized protocols is also a limitation of this therapy, which indicates the demand for more research and investigation for its constitution. The publication of protocols is of vital importance to reduce costs and fourth dimension that can be shared by the scientific community, in which the strengths and weaknesses are listed to avoid the elaboration of handling and scenarios by trial and error [56]. It is besides essential to choose the assessment instruments that permit measuring the effect of these interventions. Several have been pointed out in the literature, such every bit CAPS or PCL [57]. Further, training in VRET for therapists is essential to address the vast need for these types of interventions.

Pre-programmed virtual scenarios were used in VRET [25,34,36,39,40,41,42,43], so information technology may non be possible to create a trauma-related virtual environment that fully matches the patient'south narrative, which may lead to incongruity. Therefore, breaks in the sense of presence, besides equally in spatial or social plausibility, can occur [58]. The choice of hardware and software depends on the blazon of virtual trauma intervention; the advantages and disadvantages influence the sense of presence that is supposed to touch VR scenarios' success significantly.

The results revealed that neither spatial nor social presence was assessed in any 11 studies. All interventions with VR scenarios are based on the assumption that the sense of presence is an essential prerequisite. This aspect illustrates the demand for effective research to examine whether spatial presence is a crucial machinery for shaping the efficacy of virtual trauma interventions [59].

In that location was also no empirical evidence in any 11 studies on whether virtual trauma intervention was especially constructive for PTSD patients with imagination difficulties. Thus, future research is required to found whether virtual trauma interventions are particularly constructive for PTSD patients with imagination difficulties.

To sum up, these are our recommendations for developing and implementing VRET for PTSD: ensure the most immersive and sensory experience possible, appoint terminate-users, offer a tutorial for right operation, and rigorously evaluate the results. Moreover, the scenarios themselves must exist highly customizable because, for instance, a scenario in Republic of iraq is non at all like to a scenario in Republic of angola.

Although a systematic literature search was undertaken, some existing studies may take been excluded, as inclusion criteria limited papers to English. Moreover, our focus group was Portuguese Military machine veterans only. Therefore, circumspection should be taken when interpreting results, every bit there was some heterogeneity in the studies and samples, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, the data gathered could exist an initial pace to translate this intervention into clinical practice.

v. Conclusions

This report provided guidelines for developing an immersive VR plan–state of war scenario for War machine veterans diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. VRET can exist peculiarly useful in treating PTSD resistant to traditional exposure. It provides the power to conduct extinction training/exposures for stimuli that may exist likewise expensive or not feasible to implement in vivo, such equally virtual combat situations. Co-ordinate to this enquiry, new VRET programs should be combined with traditional therapy and must consider equally requirements the sense of presence (spatial and/or social), dynamic scenarios, realistic feeling, multisensory experience, and should stimulate the imagination. Most of the studies on VRET included 3–20 virtual exposure sessions, lasting 30–120 min. In this co-creation process, researchers must involve end-users (mainly for the formulation of narratives and content) and admission all research developed on the subject to personalise the intervention and avert inaccuracies.

We believe that the promising findings so far suggest that VRET could become a cost-efficient and effective means of providing treatment to diverse PTSD patient populations in the time to come.

Supplementary Materials

Writer Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V., A.M. and R.S.d.A.; methodology, A.Five., A.Yard. and R.Southward.d.A.; validation, A.M. and R.Due south.d.A.; formal analysis, A.Five.; investigation, A.V.; resources, A.M. and R.S.d.A.; information curation, A.V.; writing—original draft training, A.V.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and R.South.d.A.; visualization, A.V.; supervision, A.K. and R.Due south.d.A.; project administration, A.M.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors take read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) through R&D Units funding (UIDB/05210/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was canonical by the School of Health Ideals Commission (CE0064B).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Information Availability Argument

All the data analyzed in this review are included in the present article.

Conflicts of Involvement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bisson, J.I.; Wright, L.A.; Jones, K.A.; Lewis, C.; Phelps, A.J.; Sijbrandij, Grand.; Varker, T.; Roberts, N.P. Preventing the onset of mail service traumatic stress disorder. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 86, 102004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C. Post-traumatic stress disorder: The brunt to the private and to gild. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2000, 61 (Suppl. five), 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen, H.; Jacobi, F.; Rehm, J.; Gustavsson, A.; Svensson, M.; Jönsson, B.; Olesen, J.; Allgulander, C.; Alonso, J.; Faravelli, C.; et al. The size and brunt of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 21, 655–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenger, W.Due east.; Corry, N.H.; Williams, C.Southward.; Kulka, R.A.; Mulvaney-Day, N.; DeBakey, S.; Murphy, C.G.; Marmar, C.R. A Prospective Study of Bloodshed and Trauma-Related Risk Factors Among a Nationally Representative Sample of Vietnam Veterans. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 182, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-V: Transmission Diagnóstico e Estatístico das Perturbações Mentais, 5th ed.; Climepsi Editores: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Christine, H.; Nemeroff, C.B. Neurobiology of mail service-traumatic stress disorder. CNS Spectr. 2009, 14 (Suppl. 1), 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Brewin, C.R.; Andrews, B.; Valentine, J.D. Meta-assay of hazard factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 748–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botero García, C. Cerebral behavioral intervention for PTSD in Colombian combat veterans. Univ. Psychol. 2005, 4, 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Bressler, R.; Erford, B.T.; Dean, S. A Systematic Review of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL). J. Couns. Dev. 2018, 96, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Mateu, F.; Escámez, T.; Koenen, K.C.; Alonso, J.; Sánchez-Meca, J. Meta-Analyses of the five-HTTLPR Polymorphisms and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. PLoS ONE 2013, viii, e66227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.; Pair, J.; McNerney, P.J.; Eastlund, E.; Manson, B.; Gratch, J.; Hill, R.; Swartout, B. Evolution of a VR therapy awarding for Iraq war war machine personnel with PTSD. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2005, 111, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ventura Velázquez, R.Due east.; Bravo Collazo, T.M.; Hernández Tápanes, S. Trastorno por estrés postraumático en el contexto médico militar. Revista Cubana de Medicina Militar 2005, 34, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C.; Ge, Y.; Tang, B.; Liu, Y.; Kang, P.; Wang, M.; Zhang, L. A Meta-Analysis of Hazard Factors for Combat-Related PTSD amongst Military Personnel and Veterans. PLoS ONE 2015, ten, e0120270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Ganeshamoorthy, S.; Myers, J. Risk factors associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in US veterans: A cohort study. PLoS 1 2017, 12, e0181647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrajão, P.C.; Oliveira, R.A. Zipper Patterns as Mediators of the Link Between Combat Exposure and Posttraumatic Symptoms: A Study Amongst Portuguese War Veterans. Mil. Psychol. 2015, 27, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paige, L.; Renshaw, K.D.; Allen, Eastward.S.; Litz, B.T. Deployment trauma and seeking treatment for PTSD in US soldiers. Mil. Psychol. 2019, 31, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, Thou.; Jonas, D.E.; Forneris, C.A.; Wines, C.; Sonis, J.; Middleton, J.C.; Feltner, C.; Brownley, Yard.A.; Olmsted, K.R.; Greenblatt, A.; et al. Psychological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-assay. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 43, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, L.E.; Sprang, K.R.; Rothbaum, B.O. Treating PTSD: A Review of Evidence-Based Psychotherapy Interventions. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. Clinical Practise Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). 2017. Available online: https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- International Gild for Traumatic Stress Studies. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Prevention and Handling Guidelines: Methodology and Recommendations. 2018. Available online: http://www.istss.org/treating-trauma/new-istss-prevention-and-treatment-guidelines.aspx (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- National Establish for Health and Care Excellence. Postal service-Traumatic Stress Disorder NG116. 2018. Available online: https://www.squeamish.org.uk/guidance/ng116 (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Eshuis, L.; van Gelderen, M.; van Zuiden, M.; Nijdam, Grand.; Vermetten, E.; Olff, Thousand.; Bakker, A. Efficacy of immersive PTSD treatments: A systematic review of virtual and augmented reality exposure therapy and a meta-analysis of virtual reality exposure therapy. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 143, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenen, 1000.C.; Ratanatharathorn, A.; Ng, L.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Bromet, E.J.; Stein, D.J.; Karam, East.Grand.; Meron Ruscio, A.; Benjet, C.; Scott, K.; et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 2260–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamito, P.; Oliveira, J.; Pacheco, J.; Morais, D.; Saraiva, T.; Lacerda, R.; Baptista, A.; Santos, N.; Soares, F.; Gamito, L.; et al. Traumatic encephalon injury memory training: A virtual reality online solution. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2011, ten, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, E.B.; Chrestman, K.R.; Gilboa-Schechtman, E. Prolonged Exposure Therapy for Adolescents with PTSD Emotional Processing of Traumatic Experiences, Therapist Guide; Oxford Academy Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E.B.; McLean, C.P.; Brown, Fifty.A.; Zang, Y.; Rosenfield, D.; Zandberg, 50.J.; Ealey, W.; Hanson, B.S.; Hunter, L.R.; Lillard, I.J.; et al. The effects of a prolonged exposure workshop with and without consultation on provider and patient outcomes: A randomized implementation trial. Implement. Sci. 2020, xv, one–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ready, D.J.; Pollack, S.; Rothbaum, B.O.; Alarcon, R.D. Virtual Reality Exposure for Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J. Beset. Maltreatment Trauma 2006, 12, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbaum, B.O.; Hodges, 50.F.; Set, D.; Graap, G.; Alarcon, R.D. Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for Vietnam Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2001, 62, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, C.Eastward.; Miller, D.M.; Akande, C.A.; Lok, B.; Marsiske, M.; Halan, S. 5-Mart, a Virtual Reality Grocery Store: A Focus Group Report of a Promising Intervention for Balmy Traumatic Brain Injury and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 98, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miloff, A.; Lindner, P.; Hamilton, W.; Reuterskiöld, L.; Andersson, G.; Carlbring, P. Unmarried-session gamified virtual reality exposure therapy for spider phobia vs. traditional exposure therapy: Report protocol for a randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. Trials 2016, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Due south.; Kim, E. The Use of Virtual Reality in Psychiatry: A Review. J. Korean Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 31, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.Yard. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, Southward.H.; Blackness, N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the cess of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health intendance interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1998, 52, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Set, D.J.; Gerardi, R.J.; Backscheider, A.G.; Mascaro, North.; Rothbaum, B.O. Comparing virtual reality exposure therapy to present-centered therapy with xi US Vietnam veterans with PTSD. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2010, thirteen, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.S.; Difede, J.; Rothbaum, B.O.; Reger, G.; Spitalnick, J.; Cukor, J.; Mclay, R. Development and early evaluation of the Virtual Republic of iraq/Transitional islamic state of afghanistan exposure therapy system for combat-related PTSD. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1208, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reger, G.M.; Holloway, K.K.; Candy, C.; Rothbaum, B.O.; Difede, J.; Rizzo, A.A.; Gahm, Grand.A. Effectiveness of virtual reality exposure therapy for agile duty soldiers in a military mental wellness clinic. J. Trauma. Stress 2011, 24, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLay, R.N.; Woods, D.P.; Webb-Spud, J.A.; Spira, J.L.; Wiederhold, M.D.; Pyne, J.Thou.; Wiederhold, B.Thou. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Virtual Reality-Graded Exposure Therapy for Mail service-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Active Duty Service Members with Combat-Related Postal service-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyahira, S.D.; Folen, A.R.; Hoffman, H.G.; Garcia-Palacios, A.; Spira, J.50.; Kawasaki, Yard. The effectiveness of VR exposure therapy for PTSD in returning warfighters. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2012, 181, 128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum, B.O.; Price, M.; Jovanovic, T.; Norrholm, S.D.; Gerardi, M.; Dunlop, B.; Davis, M.; Bradley, B.; Duncan, E.J.; Rizzo, A.; et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind Evaluation ofd-Cycloserine or Alprazolam Combined With Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Republic of iraq and Transitional islamic state of afghanistan War Veterans. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014, 171, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reger, G.M.; Koenen-Woods, P.; Zetocha, K.; Smolenski, D.J.; Holloway, Grand.Chiliad.; Rothbaum, B.O.; Difede, J.; Rizzo, A.A.; Edwards-Stewart, A.; Skopp, Due north.A.; et al. Randomized controlled trial of prolonged exposure using imaginal exposure vs. virtual reality exposure in active duty soldiers with deployment-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 84, 946–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLay, R.N.; Baird, A.; Webb-Murphy, J.; Deal, W.; Tran, Fifty.; Anson, H.; Klam, Due west.; Johnston, S. A Randomized, Head-to-Head Report of Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, xx, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maples-Keller, J.50.; Jovanovic, T.; Dunlop, B.W.; Rauch, S.; Yasinski, C.; Michopoulos, Five.; Coghlan, C.; Norrholm, S.; Rizzo, A.S.; Ressler, K.; et al. When translational neuroscience fails in the dispensary: Dexamethasone prior to virtual reality exposure therapy increases drop-out rates. J. Anxiety Disord. 2019, 61, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van't Wout-Frank, K.; Shea, M.T.; Larson, 5.C.; Greenberg, B.D.; Philip, N.Due south. Combined transcranial directly current stimulation with virtual reality exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder: Feasibility and pilot results. Brain Stimul. 2019, 12, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozek, D.C.; Baker, S.N.; Rugo, K.; Steigerwald, 5.; Sippel, 50.M.; Holliday, R.; Roberge, E.G.; Held, P.; Mota, Due north.; Smith, N.B. Addressing Co-occurring Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Evidence-based Psychotherapies for Adults: A Systematic Review. PsyArXiv 2021. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.; Reger, G.; Gahm, Thousand.; Difede, J.; Rothbaum, B.O. Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for Gainsay-Related PTSD. In Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; Springer: Singapore, 2009; pp. 375–399. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, B.; Baños, R.K.; Botella, C. Virtual reality and stimulation of touch and odour for inducing relaxation: A randomized controlled trial. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, ane–viii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maples-Keller, J.L.; Bunnell, B.Due east.; Kim, S.-J.; Rothbaum, B.O. The Employ of Virtual Reality Technology in the Treatment of Anxiety and Other Psychiatric Disorders. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2017, 25, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerald, J. The VR Book: Human-Centered Blueprint for Virtual Reality; Morgan & Claypool: San Rafael, CA, Us, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, S.; Foa, E. Emotional Processing Theory (EPT) and Exposure Therapy for PTSD. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2006, 36, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smelser, N.J.; Baltes, P.B. (Eds.) International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Norr, A.M.; Smolenski, D.J.; Reger, G.M. Effects of prolonged exposure and virtual reality exposure on suicidal ideation in active duty soldiers: An examination of potential mechanisms. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 103, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, A.; Pair, J.; Graap, G.; Manson, B.; McNerney, P.J.; Wiederhold, B.; Wiederhold, Thou.; Spira, J. A virtual reality exposure therapy application for Iraq State of war military machine personnel with post traumatic stress disorder: From preparation to toy to treatment. NATO Secur. Sci. Ser. Eastward Hum. Soc. Dyn. 2006, six, 235. [Google Scholar]

- Knaust, T.; Felnhofer, A.; Kothgassner, O.D.; Höllmer, H.; Gorzka, R.-J.; Schulz, H. Virtual Trauma Interventions for the Treatment of Postal service-traumatic Stress Disorders: A Scoping Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnegie, M.; Rhee, T. Reducing Visual Discomfort with HMDs Using Dynamic Depth of Field. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2015, 35, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanney, One thousand.1000.; Unhurt, K.S.; Nahmens, I.; Kennedy, R.Due south. What to Wait from Immersive Virtual Environment Exposure: Influences of Gender, Body Mass Index, and Past Feel. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2003, 45, 504–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G. Virtual Reality in Psychotherapy: Review. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2005, 8, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F.West.; Litz, B.T.; Keane, T.M.; Palmieri, P.A.; Marx, B.P.; Schnurr, P.P. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-v) Boston; National Center for PTSD: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, M. Place illusion and plausibility can lead to realistic behaviour in immersive virtual environments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 3549–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothgassner, O.D.; Goreis, A.; Kafka, J.X.; Van Eickels, R.L.; Plener, P.L.; Felnhofer, A. Virtual reality exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1654782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure one. PRISMA flowchart of screening, exclusion, and inclusion criteria.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart of screening, exclusion, and inclusion criteria.

Figure 2. Downs and Black (1998) [33]—Checklist for assessment of the methodological quality [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44].

Effigy two. Downs and Black (1998) [33]—Checklist for assessment of the methodological quality [34,35,36,37,38,39,twoscore,41,42,43,44].

Table 3. Results of Study 2—Focus Grouping.

Table 3. Results of Study 2—Focus Group.

| VR Potential | VR Software | VR Barriers |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation; Technology combined with traditional therapy. | Dynamic scenario; Multisensory; Realistic; Immersive; Envelopment; Stimulate the imagination | Not prepared to "enter" a war scenario again. |

| Publisher'due south Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open admission commodity distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC By) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/1/464/htm

0 Response to "Peer Review Information on Virtual Reality Therapy for Ptsd"

Post a Comment